And now we are two.

We’ve always been three. The three boys, the three brothers, the three sons of Harry and Ann.

When our mother died in 1967, we were the three brothers, the three sons of Harry.

When our father died in 1998, we were just the three brothers.

And now we are two.

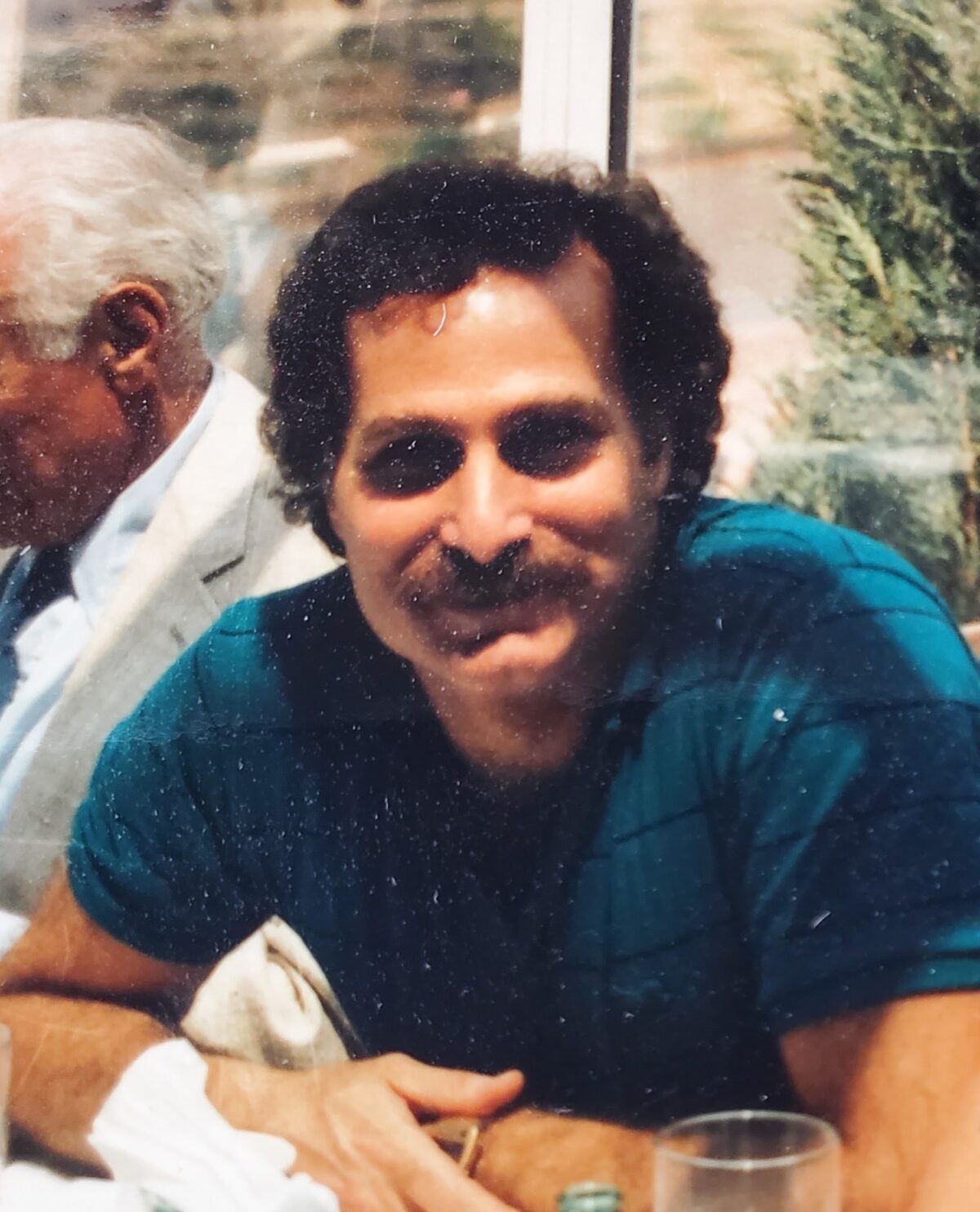

Jay, my oldest brother, died Wednesday morning after a long and painful battle with multiple myeloma. He was more than a man, a doctor, a father, husband, grandfather and brother; he was a force of nature. Although his death was a long time coming, I am still, I confess, surprised. You see, for the longest time, Jay had no intention of dying. He was used to winning. Throughout his life, he drove himself mercilessly in order to be the best at whatever he did. He was first cute and then handsome, and he chose to skip the awkward adolescent stage that most of us had to endure. He was a star athlete (state javelin champ), a star student, a star dental-then-oral-surgery-then medical student, and a star doctor of emergency medicine. His star did indeed shine bright, and everyone who met him had the option to bathe in that light or be blinded by it. No one was indifferent to Jay.

Jay was also, when he wanted to be, a bad boy. He was a skilled puppet-master and prankster who, when the opportunity arose, found great pleasure in stirring things up and watching what happened, all while appearing an innocent bystander. Particularly as a young man, he reveled in getting away with as much as he could.

Jay was the alpha of alphas. He was a proud father and grandfather who, with his wife, was parenting his third generation. To those of us in his orbit, he was extremely loving, involved, generous, and helpful but could, at times, be brutal. No behavior under his watch escaped comment if inconsistent with what Jay deemed the best way to behave. With his extraordinary intelligence and intuition, he was usually right; and he often didn’t understand why people didn’t always respond gratefully to his clear-headed advice and attempts at modification.

After all, he was Jay.

Watching Jay decline from a robust, handsome, powerful and sexy man to a frail, skeletal old man was painful, as is often the case with cancer patients. While many people spend their final months coming to terms with death and attempting to connect with their inner selves, Jay refused; to do so would be to admit defeat. He prolonged his own suffering, yet he never complained. As a doctor, he understood exactly what the lab tests and images were showing, but he kept hoping, even demanding, any and every intervention which might keep him in this world a bit longer. More than once, he canceled his hospice care in a valiant attempt to stay alive, and I was worried that, rather than dying peacefully in his sleep, he would, in yet another moment of crisis, suffer the pain, stress and fear of an EMT’s desperate attempts to revive him.

I shouldn’t have worried. Jay knew what he was doing. He took the time he needed to prepare himself and others, made sure we all had time to rush over one more time to say goodbye, and, while his wife was driving their grandchild to school, took his final breath and died. At home. In his bed. His way.

After all, he was Jay.